This week I chose to play Firewatch, a game almost exclusively driven by the narrative. The tasks you must complete involve very little skill and are rewarded buy unlocking a new portion of the narrative. I personally really enjoyed it because these are the types of games I like to play. In fact, I enjoyed it so much that I ended up finishing the entire game in one day.

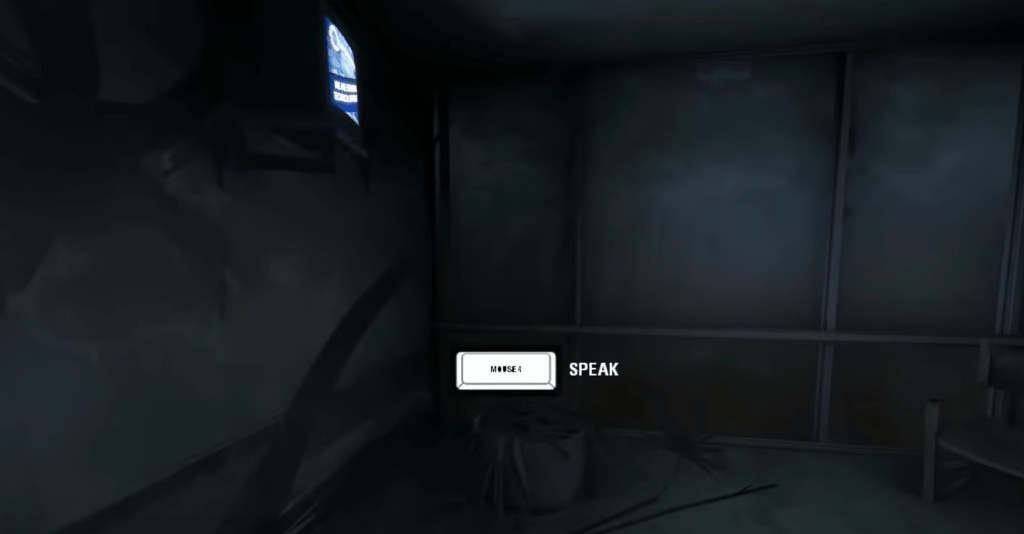

The first thing I’d like to touch on is the avatar vs character debate as brought up in the Shaw reading (Shaw, N/A). In Firewatch, because of the lack of customization, it can be concluded that Henry is a character and not an avatar. Also in this game specifically, you never actually see a person. Not your own character, not Delilah (despite conversing with her the whole game), and not Ned (even when he locks you in the cave). The only glimpse of humanity you see is your own character’s hands and occasionally legs. In class, we discussed the disparity between identifying with vs identifying as a character. In this game particularly it was hard for me to identify with the character I was playing as for a few reasons:

- I’m a young female and Henry is an older adult male

- The character design is more caracaturism versus the environment which is photorealistic

I also want to touch on a point that Shaw talked about, “Avatar-Player relationships can be quite powerful and self-referential in massively multiplayer online role-playing games.” (Shaw, N/A) This is a feeling I frequently experience when playing games, and also greatly experienced in playing Firewatch, despite the lack of customization. I found myself starting to look out for Henry, purposely choose options and routes that would be the safest for him, and consider what he would really say when looking at the dialogue. This kind of narrative game really pulls in the player to feel close to the characters.

Going back to class, we discussed Celia Pearce’s 6 narrative elements. After playing through Firewatch, I see strong alignment with #6, or ‘the story system’. This game has no outright rules besides mechanically. The player is instructed of what to do and not do by the narrative of the game. Thinking about it now, I really could go wherever I want and explore wherever I want in the forest in Firewatch but I don’t. Why? Because by following the unspoken rules of where and what my character is supposed to be doing, I get rewarded with pieces of the narrative puzzle.

Overall, this game is a perfect example of narratology and its effect on the player and they interact with the game world.

Shaw, Adrienne. Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture.